Publications

Under what conditions do rebels succeed in establishing functional institutions in state-dominated areas? Canonical theories of rebel governance and state formation insist that territorial control is a necessary precondition for the development of governing institutions. Yet despite growing recognition that this claim is empirically incorrect and theoretically limiting, we lack knowledge about the conditions under which rebels succeed in governing civilians in areas where the state dominates. We argue that low state governance responsiveness towards rebel constituencies enables insurgents to overcome the challenges associated with establishing institutions in state-dominated areas. Low state responsiveness increases popular demand for insurgent institutions, decreases the costs associated with governing, and enables insurgents to collude with civilians to hide their institutions. Case studies from Ireland, South Africa, and Algeria illustrate our propositions. Our findings deepen knowledge on how rebels govern and expand their territorial reach, and shed light on alternative trajectories of state formation.

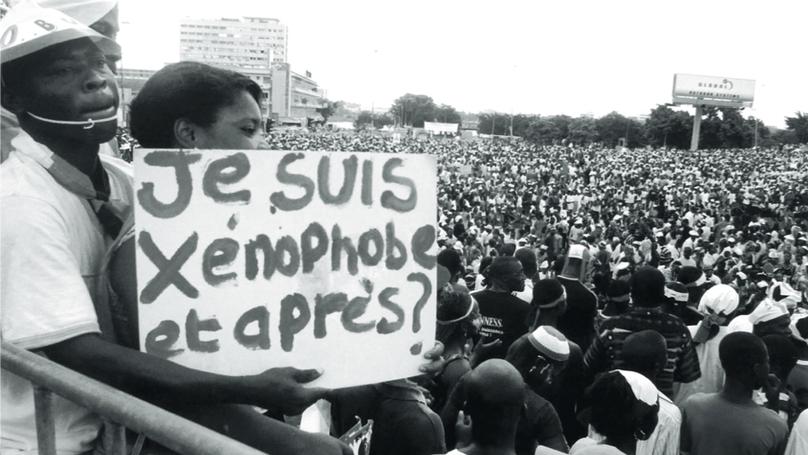

How does civilian protest shape civil war dynamics? Existing research shows that civilian protests against violence and war contribute to peace and restrain violence against civilians. There is less research on civilian protests that are at odds with peaceful conflict resolution, such as protests to salute armed actors, advocate against peace agreements, and oppose peacekeepers. This study develops a novel typology of wartime civilian protest that brings together protests to different ends, and theorizes the heterogeneous effects of protest on civil war dynamics. Using quantitative and qualitative evidence from new disaggregated and georeferenced event data from Côte d’Ivoire, the study demonstrates that—contingent on certain demands—protests were associated with violence against civilians, violence involving peacekeepers, and failed conflict resolution. These findings contribute new knowledge on how civilians shape the dynamics of civil war, and caution that nonviolent civilian action may not only be a force for de-escalation and peace.

Violent communal conflicts between identity-based groups are a severe threat to human security and development. While most communal conflicts take place in civil war-affected countries, communal conflict is not an inevitable byproduct of civil war. What explains communal peace in civil war? Existing research tends to overlook interlinkages between communal conflict and civil war, meaning that knowledge on how armed groups exacerbate or mitigate communal conflicts is limited. Combining insights from research on communal conflict and non-state armed groups, this study proposes that communal conflicts are less severe in areas controlled by legitimacy-seeking armed groups that seek acceptance for its political authority and right to rule from domestic and international audiences. Legitimacy-seeking armed groups have greater incentives to develop institutions and practices that prevent both communal conflict onset and escalation, which helps keep communal peace. The study examines the argument through a natural experiment in western Côte d’Ivoire, where more legitimacy-seeking and more legitimacy-indifferent armed groups came to control proximate and highly comparable communities because of an arbitrary ceasefire line. Using process-tracing to analyze unique interview and archival sources, the study demonstrates that communal conflicts were far deadlier in areas controlled by the more legitimacy-indifferent militias than in areas controlled by the more legitimacy-seeking Forces Nouvelles rebel group. These findings highlight that armed groups can be both agents of wartime disorder and order, and contribute new insights on communal peace in the shadow of civil war.

How, and under what conditions, does electoral violence influence voter turnout? Existing research often presumes that electoral violence demobilizes voters, but we lack knowledge of the conditions under which violence depresses turnout. This study takes a subnational approach to probe the moderating effect of local incumbent strength on the association between electoral violence and turnout. Based on existing work, I argue that electoral violence can reduce voter turnout by heightening threat perceptions among voters and eroding public trust in the electoral system, thereby raising the expected costs of voting and undermining the belief that one’s vote matters. Moreover, I propose that in elections contested across multiple local rather than a single national voting district, the negative effect of electoral violence on turnout should be greater in districts where the incumbent is stronger. This is because when the incumbent is stronger, voters have lesser strategic and purposive incentives to vote than voters in localities where the opposition is stronger. I test the argument by combining original subnational event data on electoral violence before Côte d’Ivoire’s 2021 legislative elections with electoral records. The results support the main hypothesis and indicate that electoral violence was associated with significantly lower voter turnout in voting districts where the incumbent was stronger, but not where the opposition was stronger. The study contributes new knowledge on the conditions under which electoral violence depresses voter turnout, and suggests that voters in opposition strongholds can be more resilient to electoral violence than often assumed.

Why is rebel governance more responsive in some areas than in others? In recent years, scholars have started to examine the determinants of rebel governance. Less attention has been given to explaining variation in the responsiveness of rebel governance, that is, the degree to which rebels are soliciting and acting upon civilian preferences in their governance. This article seeks to address this gap by studying local variation in rebel responsiveness. I argue that rebel responsiveness is a function of whether local elites control clientelist networks that allow them to mobilize local citizens. Strong clientelist networks are characterized by local elite control over resources and embeddedness in local authority structures. In turn, such networks shape local elites’ capacity for mobilizing support for, or civil resistance against, the rebels, and hence their bargaining power in negotiations over rebel governance. Drawing on unique interview and archival data collected during eight months of fieldwork, as well as existing survey data, the study tests the argument through a systematic comparison of four areas held by the Forces Nouvelles in Côte d’Ivoire. The analysis indicates that the strength of local elites’ clientelist networks shapes rebel responsiveness. Moreover, it provides support for the theorized civil resistance mechanism, and shows that this mechanism is further enhanced by ethnopolitical ties between civilians and rebels. These findings speak to the burgeoning literature on rebel governance and to research on civil resistance. In addition, the results inform policy debates on how to protect civilians in civil war.